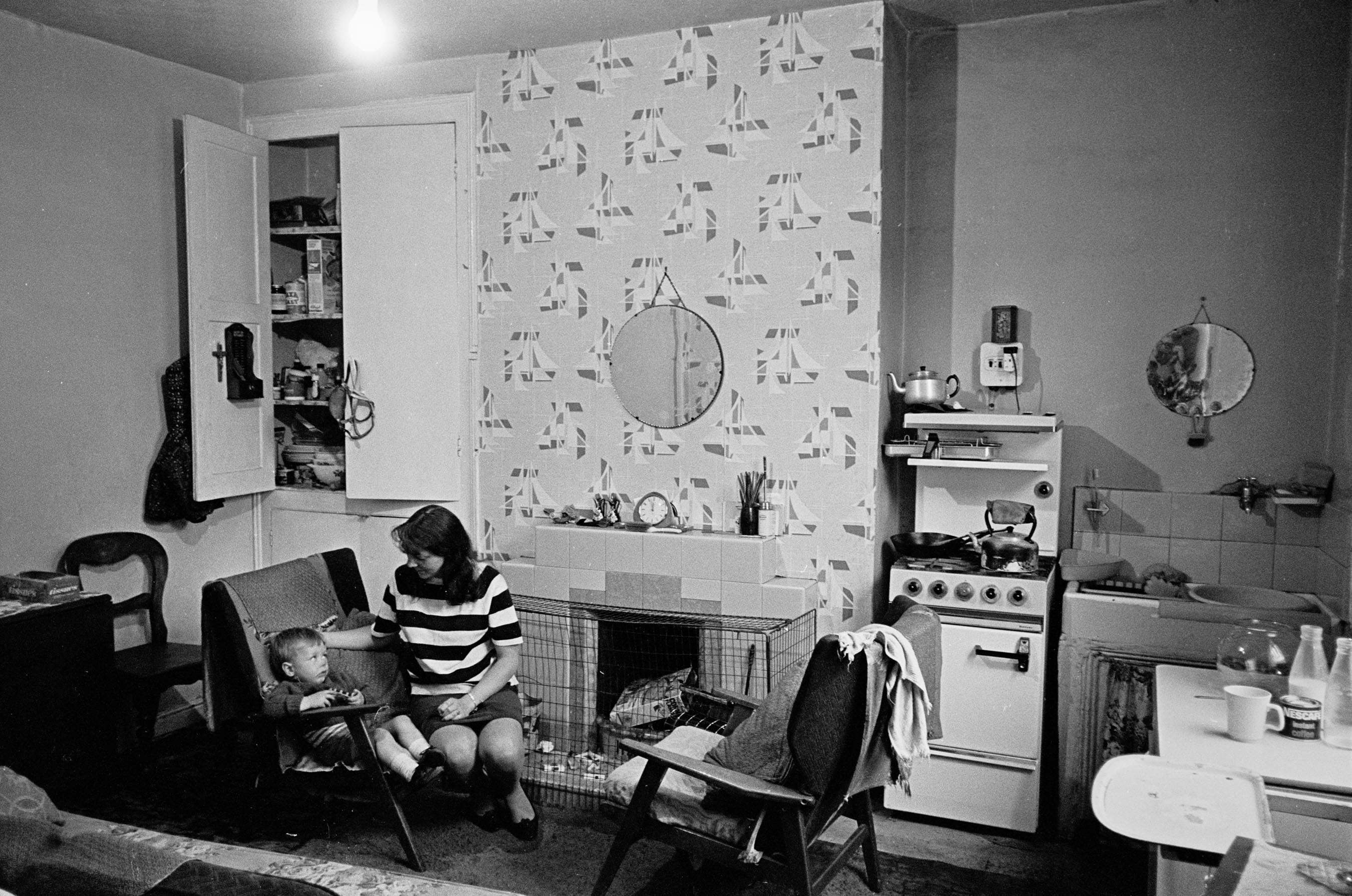

Another criticism of Lindert’s and Williamson’s optimistic findings is that their results were for workers who earned wages. John Brown found that much of the rise in real wages in the factory districts could be explained as compensation for poor working and living conditions. What proportion of the rise in urban wages reflected compensation for worsening urban squalor rather than true increases in real incomes? Williamson-using methods developed to measure the ill effects of twentieth-century cities-found that between 8 and 30 percent of the higher urban wages could be attributed to compensation for the inferior quality of life in English cities. Wages were higher in English cities than in the countryside, but rents were higher and the quality of life was lower. Other researchers have speculated that the largely unmeasured effects of environmental decay more than offset any gains in well-being attributable to rising wages. In the Feinstein series, real wages rose much more slowly than in the Lindert-Williamsons series.

Charles Feinstein produced an alternative series of real wages based on a different price index. Other economists challenged Lindert’s and Williamson’s optimistic findings. No economist today seriously disputes the fact that the industrial revolution began the transformation that has led to extraordinarily high (compared with the rest of human history) living standards for ordinary people throughout the market industrial economies. Ashton pointed out in 1948, the industrial revolution meant the difference between the grinding poverty that had characterized most of human history and the affluence of the modern industrialized nations. The ideological underpinnings of the debate eventually faded, probably because, as T. The defenders, or optimists, saw nineteenth-century England as the birthplace of a consumer revolution that made more and more consumer goods available to ordinary people with each passing year. The critics, or pessimists, saw nineteenth-century England as Charles Dickens’s Coketown or poet William Blake’s “dark, satanic mills,” with capitalists squeezing more surplus value out of the working class with each passing year.

At one time, behind the debate was an ideological argument between the critics (especially Marxists) and the defenders of free markets.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)